Wladyslaw Szpilman plays Nocturne in C sharp minor by F. Chopin

.

.

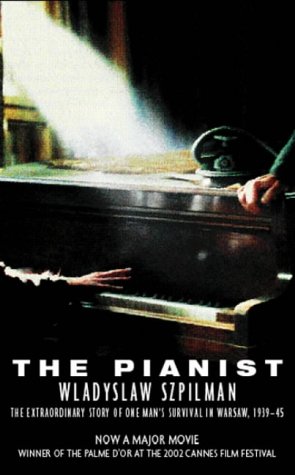

THE PIANIST

Los Angeles Times Bestsellers List BEST NONFICTION OF 1999

"It's the story I've been looking for for years..." Roman Polanski

Wladyslaw Szpilman plays Nocturne in C sharp minor by F. Chopin

.

.

THE PIANIST

Los Angeles Times Bestsellers List BEST NONFICTION OF 1999

"It's the story I've been looking for for years..." Roman Polanski

international herald tribune

The son of the Polish Holocaust survivor who was the subject of Roman Polanski 's Oscar-winning film "The Pianist" hailed the awards as a tribute to the victims of World War II. The academy "appreciated the fate that befell my father, the total degradation of a well-known artist under war conditions," said Andrzej Szpilman , a doctor who lives in Europe and who attended the Academy Award ceremony in Los Angeles. The film tells the story of Wladyslaw Szpilman , a Jewish pianist in Warsaw. It won three Oscars: best director; best actor, and best adapted screenplay.(Wednesday, March 26, 2003)

![]()

Army Archered - senior columnist, Just for Variety

Meanwhile, Roman Polanski's "The Pianist" received a huge rave in the Jerusalem Post, with William E. Grim calling the film, "undoubtedly the greatest Holocaust film of all time," adding "'The Pianist' is a testament to the indefatigable spirit of life that refuses to go gentle into the night." He also notes Adrien Brody's performance as "stunning."

![]() From SONY Classical Germany

From SONY Classical Germany

on 30.9.2005

On 3 CD´s:

|

|

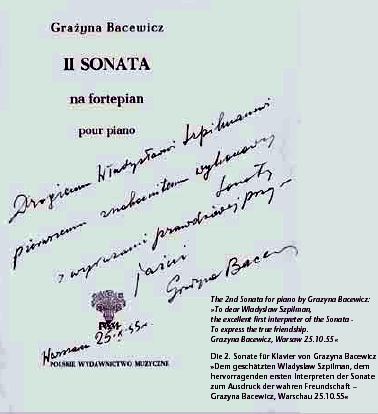

Solo recordings: Chopin, Alfred Grünfeld, Debussy, Ignaz Friedman, Szpilman, Prokofjew 7th Sonata, Bacewicz, Sonata Nr. 2 (1st publication of the world premiere in 1953)

-

-

-

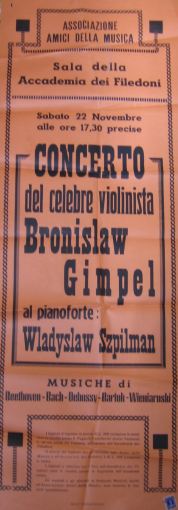

Works for Violin and Piano with Bronislaw Gimpel: Beethoven "Spring", Grieg op.45, Rathaus "Pastorale and Dance" (1st publication of the world premiere recording in 1963) and small works by Schubert, Dvorak, Wieniawski, Bloch, Prokofiew

-

-

-

The Warsaw Piano Quintet: Piano quintets by Robert Schumann and Juliusz Zarebski (1st publication of the world premiere recording 1963)

![]()

How war transforms 'Pianist'

For all of its devastating power, Roman Polanski's film The Pianist reaches a point where it doesn't entirely ring true. How could anybody emerge from five horrific years of hard labor and starvation in World War II Warsaw with such clean, crisp, emotionally unclouded renditions of Chopin?

The real-life Wladyslaw Szpilman, whose memoir was the basis of the film, didn't play that way. Even before hearing the two Szpilman discs that have hit the market amid the two-Oscar success of The Pianist, seasoned music lovers could have predicted that. Polish pianism of that period is more about shade than light.

But anyone can understand that artistic expression, even the supposedly stationary world of classical music, cannot exist in a demilitarized zone, standing apart from world events. Performances conceived, delivered and heard during a state of crisis, or in its aftermath, can be hugely different from those that are not.

Szpilman's fellow musicians - whatever side they were on during the war - changed so much over the 1940s and after that the great masterpieces they performed seemed to rewrite themselves. You can hear it in before-and-after recordings, in which one conductor beefed up the militaristic brass, and another found a conduit for psychic pain in the music's dissonances.

Similarly, the world changed after Sept. 11 - and for a while, so did the music-making. How the current war will change what we hear remains to be, well, heard.

You could argue that such changes have most to do with how we hear. But this is only partially true. I made a point of listening to the Szpilman discs (one from the independent label BCI Eclipse and the other from the German branch of Sony Classical) before and after seeing the film. What I heard didn't change, but the film explained a few things.

Szpilman, who died three years ago, was an artist of sterling pedigree, which all but guarantees his recordings won't be a redux of the David Helfgott-style compromised pianism heard in the wake of the 1996 film Shine. No, from the first notes of both Szpilman discs, you hear poetic, Old-World rubato and that warm blanket of piano tone that's missing from the film's soundtrack performances by Janusz Olejniczak.

Most arresting is a 1960 reading of Schumann's Fantasy in C major, the middle movement, which reaches an utterly singular, harrowingly intense climax. Nobody can really say this reflects Szpilman's wartime hardships, but my intuition tells me, unmistakably, that only someone who has paid rent in the abyss could conceive such phrase readings.

Nearly identical in their selection of works, the two discs differ mainly in Sony's inclusion of a CD-ROM video feature of the aging Szpilman playing Chopin's Nocturne in C sharp minor in 1980. That's where the film offers needed context. The dignity of the pianist's manner has infinitely more impact if you know that this is the piece he was playing when Polish Radio was destroyed by the Nazis and that he returned to five years later, after the Nazis had been destroyed. Without asking for the slightest bit of sympathy, he was recreating a moment that was emblematic for his country and all Jewish survivors of World War II.

David Patrick Stearns Philadelphia Courier Sun, Mar. 30, 2003

"The Pianist" Book by Wladyslaw Szpilman translated into 30 languages

Los Angeles Times Bestsellers List - The Best Books of 1999 - BEST NONFICTION OF 1999

Boston Globe - The most disturbing and moving book of the year

The Sunday Times - Biography top five & 1999 bestsellers

THE GUARDIAN - Books of the year 1999

The Economist - Our reviewers' favourites 1999

LIBRARY JOURNAL - Best Books of 1999

WLADYSLAW SZPILMAN WINS ANNUAL JEWISH QUARTERLY-WINGATE NON FICTION PRIZE 2000

London - 3rd May 2000 - The judges of the annual Jewish Quarterly-Wingate Literary Prizes tonight awarded this year's Non Fiction Prize to Wladyslaw Szpilman for The Pianist (Phoenix / Golancz). The decision was announced by author and broadcaster Frank Delaney, chairman of the judges, who had selected it earlier this evening from a shortlists of four titles: "When you read this book - and you must read it - you will never forget it. The subtext asks whether good people were on the side of the evil people and shows how the human spirit is enlarged by the knowledge of such people."

London - 3rd May 2000 - The judges of the annual Jewish Quarterly-Wingate Literary Prizes tonight awarded this year's Non Fiction Prize to Wladyslaw Szpilman for The Pianist (Phoenix / Golancz). The decision was announced by author and broadcaster Frank Delaney, chairman of the judges, who had selected it earlier this evening from a shortlists of four titles: "When you read this book - and you must read it - you will never forget it. The subtext asks whether good people were on the side of the evil people and shows how the human spirit is enlarged by the knowledge of such people."

Le Pianiste - Best book of the year 2001 Journal Lire - France

Le Pianiste - Readers price - Grand Prix by Journal ELLE - France 2002

The talented Pianist Wladyslaw Szpilman gave, with great success, a concert in the auditorium of the music conservatory on the 22nd of this month. ("Our Illustrated Newspaper" Warsaw, June 1, 1930)

First official broadcast of the Polish Television December 1951

Playing at survival in Warsaw

by Anne Applebaum Evening Standard 14 May 1999

He lives in a neat, narrow house with a small, well-kept garden. Inside his sitting room there are shelves of old books, a Bieder-meier secretaire, a polished parquet floor. Black and white photographs of old friends stand in rows on the piano; prints and framed mementoes hang from the white walls. At first glance, everything about Wladyslaw Szpilman speaks of a certain kind of Central European comfort, of a pleasantly uneventful, bourgeois life. Dressed in a tweed jacket and tie, speaking of popular music and songs, Szpilman himself initially gives off the air of someone who has lived all of his 87 years in civilised surroundings. Then, effortlessly, he moves from the familiar to the horrific.

"I looked like a wild man," he recalls. "I was dirty, unshaven, my hair was long. The German found me when I was in the ruins of someone's kitchen, looking for food. I found out later - this isn't in the book - that he was lookin g for toothpaste, but no matter. When he saw me, he asked me what on earth was I doing there ... What could I say? I couldn't say that I was Jewish, that I was hiding, that I had been in these ruins for months. I told him that this was my old flat, that I had come back to see what was left ..."

g for toothpaste, but no matter. When he saw me, he asked me what on earth was I doing there ... What could I say? I couldn't say that I was Jewish, that I was hiding, that I had been in these ruins for months. I told him that this was my old flat, that I had come back to see what was left ..."

So begins Szpilman's account of how, in the final weeks of the Second World War, having escaped the Warsaw Getto and survived months of hiding, he was rescued by a German: CaptainWilm Hosenfeld discovered him, ascertained that he was a pianist - to convince him, Szpilman played Chopin's Nocturne in C sharp minor on a battered, out-of-tune piano - and without much further ado found him a better hiding place. "He noticed something I had not seen: that just beneath the roof there was a tiny attic ..." Together, they made sure Szpilman could climb into it, and pull up the ladder afterwards.

Over the subsequent weeks, the German officer regularly brought bread to the Jewish musician, and news from the Front. Finally, in December 1944, he left him with the words: "The war will be over by spring at the latest." As Szpilman tells it now, the story sounds like a coincidence, a once-in-a-life-time piece of luck. In fact, it is merely one episode in an extraordinary story of survival, recently published in English as The Pianist. Wladyslaw Szpilman, already a famous musician and composer when the war broke out - Poles of a certain generation still know the words to his popular songs - was rescued not only by a German but by a Jewish policeman, who pulled him out of a queue of people boarding trains for Treblinka; by his talent, which kept him alive in the starving Warsaw Ghetto; and by, in his own estimate, no less than 20 Poles who smuggled him out of the Ghetto and then hid him in their flats, knowing that they and their families could be sentenced to death for helping a Jew.

In the end he survived for several months alone, perhaps the only person alive in the burnedout ruins of Warsaw, drinking water frozen in the bathtubs of empty flats and eating whatever he could find hidden in destroyed kitchens. Written in flat, almost emotionless prose, The Pianist evokes the strange mix of horror and elation Szpilman must have felt at that time. His whole family was dead, his city was in ruins, and yet, against all possible odds, he remained alive. Both the book, and the man himself, are also devoid of any desire for vengeance.

There is no finger-pointing in The Pianist, no hatred. Along with his straightforward portrait of Captain Hosenfeld, he depicts good  Jews and bad Jews, Poles who helped him and Poles who cheated him. Ideology, nationality and religion, he says now, had nothing to do with anyone's wartime behaviour: "One of the Poles who helped me first told me, 'I was an anti-Semite, but not any more.' Then he went on to risk his life by hiding me."

Jews and bad Jews, Poles who helped him and Poles who cheated him. Ideology, nationality and religion, he says now, had nothing to do with anyone's wartime behaviour: "One of the Poles who helped me first told me, 'I was an anti-Semite, but not any more.' Then he went on to risk his life by hiding me."

Although it has only now appeared in English, Szpilman first wrote his wartime memoir in 1945. In that post-war era, it appeared in poor quality bindings, on bad paper, and in a very small print run, which nevertheless sold out immediately. After that, the story was forgotten, or rather ignored. In Poland, it was never reprinted: within a few years of the war's end, Poland's communist authorities had grown touchier about the publication of a book which had a German hero, and which also contained flattering descriptions of the Polish Home Army, the wartime, anti-communist Polish underground.

Szpilman tried once or twice to have the book republished, but didn't push. He was more interested in his music, didn't consider himself a writer, and most of all had no interest in politics of any kind. "Three times they asked me to join the Communist Party, but I always said no," he says now.

Only the efforts of his son Andrzej, who lives in Germany, ensured that the book was published there two years ago, where it became a best seller, and now in Britain.

But even during its years out of print, Szpilman's story did have some unexpected effects. Among other things, it led him, through a series of chance meetings, to Frau Hosenfeld, the wife of his good German. She wrote to him in 1950, when her husband was dying in a Soviet prison camp, asking for help. Szpilman did what he could.

"I went," he says grimly, "to see Jakub Berman."

Berman was the head of the Polish secret police, and, in Szpilman's words, a criminal whom no decent person in Poland would speak to. Being a celebrity himself, Szpilman simply rang up Berman's office and said he wanted to meet him on a private matter. They met, Berman listened. Nothing came of it. Captain Hosenfeld died in his Soviet prison camp, having been tortured for claiming to have saved a Jew.

And not just one: over the years, it has emerged that Captain Hosenfeld served as guardian angel for a whole group of people, including others Jews, as well as a Polish priest. His son has been to visit Szpilman: the two of them went together to the building, now rebuilt, where the Wehrmacht officer brought bread to the Jew in hiding. Standing there on the street, the younger Hosenfeld had what Szpilman can only describe as "an attack of hysteria".

Szpilman himself does not appear prone to such violent emotions. He says he is often asked how he can bear to go on living in a country in which he saw so many people die, but he says that most of the time it doesn't bother him. Polish is his language, Poland is where he was born - "my son says there was a Szpilman here in the 15th century" - and Poland is where his music was popular, even adored.

adored.

True, he has never been to Treblinka, where his entire family died: they were on the train that he escaped. "To the end of my life," he says flatly,

"I will never forgive myself that I was unable to do anything to save them." But he has always lived in Warsaw - some of his best-loved songs are dedicated to the rebuilding of the city - despite, or perhaps because of, the things he saw there. And he does appear i n s e p a r a b l e from Warsaw, and from a certain old-fashioned aspect of the city's culture: he easily r e m i n i s c e s about Warsaw café society of the 1960s and1970s, shakes his head at today's popular music - " I can ' t understand any of the words" - and is looking forward, next year, to his fiftieth w e d d i n g anniversary. His wife, a doctor of 70 who appears no older than50, smiles graciously as she pours tea into English china cups. The horror and the terror are there, in the background, but they don't show on the surface.

Or not always. After the war, Szpilman gave occasional piano recitals at 8 Narbutta Street, in a building in central Warsaw which he helped to construct as part of a slave labour gang from the Getto. Most of the Jewish brigade who worked there were shot, once the construction had been finished, if they hadn't died already. At the end of The Pianist, Szpilman describes his feelings about returning, once again, to that terrible place:

"The building still stands, and there is a school in it now. I played to Polish children who do not know how much human suffering and mortal fear once passed through their sunny schoolroom.

"I pray they may never learn what such fear and suffering are."

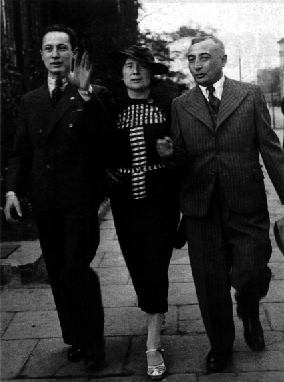

Recently discovered and only known photo of Henryk Szpilman

The "Palme d’Or" , three "Oscars" and various European film prizes were among the awards collected by "The Pianist", Roman Polanski’s film based upon Wladyslaw Szpilman’s bestseller book "The Pianist" , dealing with his "miraculous survival" (as he called it) in Warsaw during the German occupation and final destruction between 1939 and 1945. But there is more to Szpilman than being "The Pianist". He is increasingly being noticed as a composer, both of concert works and of music in a lighter vein.

To say that the music was Wladyslaw Szpilman's life-blood is more than just a poetic metaphor. The Polish composer and pianist literally owes his miraculous survival of the Holocaust to music.

Born in the Polish town of Sosnowiec on 5 December 1911, after first piano lessons Wladyslaw Szpilman continued his piano studies at the Warsaw Conservatory under A. Michalowski and subsequently at the Academy of Arts (Akademie der Kuenste) in Berlin under Arthur Schnabel and Leonid Kreutzer. He also studied composition under Franz Schreker. In 1933, he returned to Warsaw where he quickly became a celebrated pianist and a composer of both classical and popular music. On 1 April 1935 he entered Polish Radio, where he was working as a pianist performing both, classical and jazz music.

The German invasion of Warsaw on 23 September 1939 put an untimely but temporary end to Szpilman's musical career when a bomb, dropped on the studios of Polish Radio, interrupted his performance of Chopin's Nocturne in C Sharp minor. Yet despite the inevitable changes to his life, brought about by the onset of war, Szpilman refused to give up his music. His Concertino for piano and orchestra was composed while he was experiencing the hardships and deprivation of the Warsaw Getto in 1940. Time after time, Szpilman managed to escape the deportations. Even when he and his entire family were packed into cattle trucks to be sent off to Treblinka, the famous pianist was miraculously picked out and spared from the death camp. He fled to the Aryan part of the city and spent two long and agonising years in hiding, always assisted by loyal Polish friends. After the Warsaw Uprising he continued to lead the life of a recluse in the deserted ghost town. Towards the end of the war, he was discovered by a German officer of the Wehrmacht, Wilm Hosenfeld, who saved his life after listening to the starved pianist play Chopin's C Sharp minor Nocturne on the out-of tune piano of his hiding-place.

bomb, dropped on the studios of Polish Radio, interrupted his performance of Chopin's Nocturne in C Sharp minor. Yet despite the inevitable changes to his life, brought about by the onset of war, Szpilman refused to give up his music. His Concertino for piano and orchestra was composed while he was experiencing the hardships and deprivation of the Warsaw Getto in 1940. Time after time, Szpilman managed to escape the deportations. Even when he and his entire family were packed into cattle trucks to be sent off to Treblinka, the famous pianist was miraculously picked out and spared from the death camp. He fled to the Aryan part of the city and spent two long and agonising years in hiding, always assisted by loyal Polish friends. After the Warsaw Uprising he continued to lead the life of a recluse in the deserted ghost town. Towards the end of the war, he was discovered by a German officer of the Wehrmacht, Wilm Hosenfeld, who saved his life after listening to the starved pianist play Chopin's C Sharp minor Nocturne on the out-of tune piano of his hiding-place.

When Szpilman resumed his activities as the at Polish Radio in 1945, he did so by carrying on where he left off six years before: poignantly, he opened the first transmission of the station by playing, once again, Chopin's C Sharp minor Nocturne.

From 1945 to 1963 he held the position of Director of Music at Polish Radio. During these years he composed several symphonic works and about 500 songs, many of which still are popular in Poland today, including some children's songs, as well as music for radio plays and film. He also performed as a soloist and with the violinists Bronislaw Gimpel, Roman Totenberg, Ida Haendel and Henryk Szeryng. In 1963, he and Gimpel founded the Warsaw Piano Quintet with which Szpilman performed world-wide until 1986.

Wladyslaw Szpilman died on 6 July 2000 in Warsaw.

Adrien Brody accepting the Oscar Award:

..."This film would not be possible without the blueprint provided by Wladyslaw Szpilman. This is a tribute to his survival"...

Directed by Roman Polanski

Starring: Adrien Brody and an ensemble cast

Director Roman Polanski is back with his best film since Chinatown. In fact, The Pianist just might be Polanski's best film ever. It's that powerful.

Based on the autobiographical book by Wladyslaw Szpilman, The Pianist tells the story of Szpilman's struggle to survive the Nazi occupation of Poland during World War II. Szpilman, a talented Jewish pianist and composer, witnessed first-hand the horrors of the Warsaw ghetto.

The Nazis used this notorious, walled slum to imprison Polish Jews until their "resettlement" to concentration camps.

While most of his Jewish relatives and friends perished in the Holocaust, Szpilman managed to survive through sheer force of will and a number of strokes of luck. The film tells his heartbreaking survival story with unflinching honesty.

There are many fine performances in The Pianist, but it is Adrien Brody's portrayal of Szpilman that carries the film. Brody (The Thin Red Line, Summer of Sam, etc.) gives a masterful performance in this film. At times, he says more with his sad eyes than any dialogue could ever provide. He fully deserves the Oscar nomination he recently received for this multi-layered performance.

It's hard to imagine a filmmaker better suited to direct The Pianist than Polanski. His grim, existential sense of irony works perfectly with Szpilman's story. Polanski's effective direction never falls out of step with the story.

Steven Spielberg's film, Schindler's List, brilliantly captured the raw horror of the Holocaust, but The Pianist does even more than this. As well as the horror, Polanski's film also captures the tragic absurdity of the situation.

In the most powerful example of this absurdity, Szpilman and his family watch from their window as Nazi thugs enter an apartment across the street and command a Jewish family to stand up from their dinner table. When an elderly and disabled family member fails to rise from his wheel chair, the Nazis calmly throw him off the apartment's balcony to his death below. The horrific absurdity of this scene is mind-boggling. But it's also a typical Polanskian moment: In a Polanski film, the world can be a maliciously absurd place.

The film's greatest achievement is that it portrays all of the horror and insanity of the Holocaust without ever losing a sense of hope. Despite facing unimaginable cruelty and hardship, most of the Jewish characters in the film never lose their humanity. And that's the triumph of Wladyslaw Szpilman's story.

- Kenneth Hann ( www.sceneanhheard.ca Vol. 02 - Issue 08 )

Wladyslaw Szpilman

When the shells of the invading Nazis forced the closure of Polish Radio on 23 September 1939, the last live music heard was Wladyslaw Szpilman's performance of Chopin's C sharp minor Nocturne. When broadcasting was resumed in 1945, it was again Szpilman who initiated the transmissions, with the same Chopin nocturne. (Around the same time, rather less high-mindedly, BBC television resumed an interrupted Mickey  Mouse cartoon.) What happened to Szpilman in the interim formed the stuff of one of the most harrowing of all accounts of Jewish life under the Nazis, in a book published last year as The Pianist that immediately climbed to the top of the international bestseller lists --- hardly surprisingly: it is a compelling, harrowing masterpiece.

Mouse cartoon.) What happened to Szpilman in the interim formed the stuff of one of the most harrowing of all accounts of Jewish life under the Nazis, in a book published last year as The Pianist that immediately climbed to the top of the international bestseller lists --- hardly surprisingly: it is a compelling, harrowing masterpiece.

Szpilman wrote Death of a City (the initial title of his memoir) in 1945 more or less as therapy --- to put his memories down on paper and thus somehow to externalise them. In doing so he revealed that he was a masterly writer: his text matches a sharp eye for detail and for human character with a complete absence of self-pity and of sanctimony.

For the first two years of the occupation Szpilman played in the bars and cafés that continued to open for business behind the walls of the getto, sealed off from the rest of Warsaw on 15 November 1940. Szpilman records life there with dignity and dispassion. He recalls watching the SS forcing a group of prisoners out of a building:

They switched on the headlights of their car, forced their prisoners to stand in the beam, started the engines and made the men run ahead of them in the white cone of light. We heard convulsive screaming from the windows of the building, and a volley of shots from the car. The men running ahead of it fell one by one, lifted into the air by the bullets, turning somersaults and describing a circle, as if the passage from life to death consisted of an extremely difficult and complicated leap.

Time and again, chance dictated that Szpilman escape death. The end seemed finally to have come when he and his family were ordered to turn up at the Umschlagsplatz where, skirting the rotting corpses around them, they were to be herded onto trains headed for the gas chambers. Szpilman's last memory of his family is movingly understated:

At one point a boy made his way through the crowd in our direction with a box of sweets on a string round his neck. He was selling them at ridiculous prices, although heaven knows what he was going to do with the money. Scraping together the last of our small change, we bought a single cream caramel. Father divided it into six parts with his penknife. That was our last meal together.

ridiculous prices, although heaven knows what he was going to do with the money. Scraping together the last of our small change, we bought a single cream caramel. Father divided it into six parts with his penknife. That was our last meal together.

But as the Szpilmans were being crammed onto the train, one of the Jewish policemen grabbed Wladyslaw by the collar, yanked him out of the throng and refused to let him through to rejoin his family on the journey to death. Szpilman continued to avoid death's clutches, surviving against all odds, often half-starved and usually alone, hidden in obscure corners of bombed, burned or empty buildings, intermittently helped by Polish friends risking their own lives to bring him food or find him shelter: helping a Jew automatically brought a death sentence. The strangest twist in Szpilman's strange story came at its end: he was discovered by a German officer who, after Szpilman had given proof of his profession by playing that same C sharp minor Nocturne on an abandoned piano, hid him and brought him food and an eiderdown for warmth.

Not the least extraordinary aspect of Szpilman's book is the complete lack of the indignation and anger that anyone writing immediately after such years of hell might reasonably be expected to allow himself. Yet even the grim vignettes of pointless death that are studded through his text don't draw judgement --- perhaps because none was necessary:

A boy of about ten came running along the pavement. He was very pale, and so scared that he forgot to take off his cap to a German policeman coming towards him. The German stopped, pulled his revolver without a word, put it to the boy's temple and shot. The child fell to the ground, his arms flailing, went rigid and died. The policeman calmly put his revolver back in its holster and went on his way. I looked at him; he did not even have particularly brutal features, nor did he appear angry. He was a normal, placid man who had carried out one of his many minor daily duties and put it out of his mind again at once, for other and more important business awaited him.

A boy of about ten came running along the pavement. He was very pale, and so scared that he forgot to take off his cap to a German policeman coming towards him. The German stopped, pulled his revolver without a word, put it to the boy's temple and shot. The child fell to the ground, his arms flailing, went rigid and died. The policeman calmly put his revolver back in its holster and went on his way. I looked at him; he did not even have particularly brutal features, nor did he appear angry. He was a normal, placid man who had carried out one of his many minor daily duties and put it out of his mind again at once, for other and more important business awaited him.

Death of a City was published in Poland in 1946 and soon suppressed by the Communists because, as Wolf Biermann surmises in an Epilogue to The Pianist, it "contained too many painful truths about the collaboration of defeated Russians, Poles, Ukrainians, Latvians and Jews with the German Nazis". More likely, it was Szpilman's record of the suffering of the Jews that required silencing – after all, the Jews could hardly expect a warmer welcome in Stalin's empire than in Hitler's: when Stalin died, in March 1953, he was already assembling the transport for his own eastwards "resettlement" of the Jews, and his own death prevented would probably have been a second Holocaust. And so it was only after the collapse of the Soviet bloc that, thanks to the efforts of Szpilman's son, publication became possible.

Szpilman's initial training as a pianist was in the Chopin School of Music in Warsaw under Josef Smidowicz and Aleksander Michalowski, both of them former students of Liszt. In 1931 he enrolled at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin, studying piano under two of the most distinguished players of the day, Arthur Schnabel and Leonid Kreuzer, and composition under Franz Schreker, the renowned composer of Der ferne Klang and other similarly successful operas. On his return to Poland in 1933 he formed a highly successful duo with the violinist Bronislaw Gimpel that f ormed the basis, 29 years later, of the Warsaw Piano Quintet, whose tours soon earned it a reputation as an ensemble of world standing; Szpilman played with the Quintet until 1986.

ormed the basis, 29 years later, of the Warsaw Piano Quintet, whose tours soon earned it a reputation as an ensemble of world standing; Szpilman played with the Quintet until 1986.

Szpilman's own early compositions include a violin concerto and a symphonic suite, The Life of Machines, and when the Nazis invaded he was engaged on a Concertino for piano and orchestra --- a jazz-flavoured, Gershwinesque piece remarkably good-natured for the circumstances of its origin. The score went with him from hiding-place to hiding-place before he had to sacrifice it to survival; he reconstructed it after the War. His light music was particularly successful: for decades the Poles sang tunes from his three musicals, 50---60 children's songs and 600-odd chansons as they went about the business of their daily lives.

A CD released in 1998 by the German label Alina (run by Szpilman's son, Andrzej) testifies to both his fluency as a composer and his excellence as a pianist --- and it includes an archive recording of that life-saving Chopin nocturne. Six more CDs of Szpilman as both performer and composer are scheduled for release in Poland in the autumn. With luck his last-minute fame as a writer will bring his music the wider currency he would have wished for it during his lifetime.

MARTIN ANDERSON Independent, 14 August 2000

Wladyslaw Szpilman, pianist and composer, born 5.December.1911, Sosnowiec, Poland; married Halina Grzecznarowski, 2 sons; died Warsaw, 6 July 2000.

In tune with history

The Pianist book is a vivid look at occupied Poland Author's son worked years to get it published

Films, if they are resonant enough, have a way of sending people back to their source materials, a phenomenon for which the publishing industry is duly grateful. Who was that character we see for a few seconds? What really happened after the events portrayed in the movie?

The truth is, we will never trust movies the way we tend to trust books to deliver the real story.

A glance at the New York Times best seller list shows that Virginia Woolf's 1925 novel Mrs. Dalloway, the inspiration forThe Hours, is No. 11 on the fiction list and climbing. Catch Me If You Can, the memoirs of conman Frank Abagnale, The Gangs Of New York by Herbert Asbury (first published in 1928), and The Pianist by Wladyslaw Szpilman are non-fiction best sellers.

The last of these is worth a closer look. Before Roman Polanski's The Pianist became possibly the best film ever made about the Holocaust, before it won the Palme d'Or at Cannes and garnered seven Oscar nominations, this story of the against-all-odds survival of the Jewish musician in German-occupied Poland was a book with an unusual publishing history.

Szpilman witnessed the full horror of the Warsaw Getto then saw his parents, sisters and brother forced by the SS into cattle cars bound for certain death in Treblinka.

Miraculously pulled out of the lineup for the train and urged to flee by a Jewish collaborationist policeman, he was assigned to work on a building crew in the ghetto, then escaped and hid for more than two years in the progressively more starved and ruined city with the help of members of the Polish resistance. Near the end of the war, he was discovered in an attic and protected by a nameless Wehrmacht officer, who brought him bread and jam and an eiderdown for warmth.

Szpilman, who died in 2000 at the age of 88, wrote down this amazing story immediately after the liberation of Poland, which gives it unparalleled authenticity. More remarkable is his complete lack of indignation, anger or self-pity in the telling.

"My father was told by a doctor that he should see a psychiatrist because of the trauma he went through. Or he could do auto-therapy — writing it down," Szpilman's son Andrzej explains over the phone from Hamburg, Germany.

"He was working as music director for Polish radio and he had a secretary. He dictated the book to her. It took him 3 1/2 months."

The memoir was published in Polish in 1946 as Smierc Miasta meaning Death Of A City, then went out of print.

"In the 1960s the director of a publishing house approached my father and said he would like to print the book again but he had to ask permission of the Communist Party central committee. Two weeks later, he came back and said the committee said `No.' They gave no reason, but I think they did not want to touch the question of minorities and also, the Soviets were supposed to be our friends."

The book, which ends with the kindly German army officer getting captured by Soviets, presents too complex a view of human nature for any dictatorship to stomach. Poles, Jews, Germans as well as the Russian liberators are all shown to be capable of evil as well as decency.

In 1950, Wladyslaw Szpilman married a doctor, Halina Grzecznarowski, and had two sons. Andrzej, 46, who plays the violin but is a dental surgeon by profession, is the more musical son, devoted to the memory of his father. (An elder, Christopher, is a history professor living in Japan.)

That the book got a new lease on life after 50 years and found its way to Roman Polanski was due largely to Andrzej's persistence.

Andrzej was living in Germany after the fall of communism in Poland, teaching dentistry at the university in Hamburg and producing records on the side. He recorded the poet Wolf Biermann, whom he describes as "the German Bob Dylan," and told him about his father.

Andrzej was living in Germany after the fall of communism in Poland, teaching dentistry at the university in Hamburg and producing records on the side. He recorded the poet Wolf Biermann, whom he describes as "the German Bob Dylan," and told him about his father.

Biermann asked around and discovered that a Polish-German translator had, in fact, translated and published a couple of chapters from Szpilman's out-of-print book. "I paid her to finish the whole book so that my friend Wolf could read it," recalls Andrzej.

"I met a publisher in Hamburg at a party and told her I had a translation of the book, and it was available. She said right away, `I'll take it,'" he says. It came out in Germany in `98 with Biermann's epilogue.

Andrzej ran into a friend in Monte Carlo who told him of an English literary agent, Christopher Little, who might be able to arrange for British publication. Andrzej sent him the book, not realizing he had lucked out: Christopher Little, who represents J.K. Rowling, of Harry Potter fame, is the hottest British literary agent. The Pianist was translated by Anthea Bell and published by Victor Gollancz in 1999, with Wladyslaw and Andrzej coming to England for the book's launch. Picked as one of the year's best books by The Sunday Times, The Guardian and The Economist, The Pianist was sold by Christopher Little to 21 other countries including, at last, Poland. The book sold 320,000 copies in France and 200,000 in Poland, where Szpilman was best known as a composer of popular songs.

"If you ask me why I did it (republish his father's book) I felt we had to bring this message to the people," says Andrzej. "There is a strong ethnic nationalism coming back in Europe — this book is warning."

The current paperback version of the book (distributed in Canada by McArthur & Co.) includes extracts from the diary of Capt. Wilm Hosenfeld, a devout Catholic who, it turns out, saved several Jews besides Szpilman. It was from one of these other Jews that Szpilman learned his name in 1950 and tried to get him out of the prisoner-of-war camp in Russia, where he was tortured and died.

According to Andrzej Szpilman, Polanski's lawyer bought the book and sent it to Polanski with a note: "Here is your next movie." Little sold film rights to Polanski in Jan. 2000.

"We saw the movie for the first time in Cannes, with my mother and brother. My son, who is 10, had a very small part in it," says Andrzej. "It was very moving, a shock. Adrien Brody is very like my father. Since then I have seen it 15 times. In Poland 3,500 people saw the premier and applauded for 20 minutes. The Polish president and prime minister were there." Hosenfeld's children were also there.

These days, Andrzej Szpilman has taken leave of his dental surgery practice to devote himself entirely to making sure his father's music legacy — three musicals, around 50 children's songs and 600 pop tunes — is not lost.

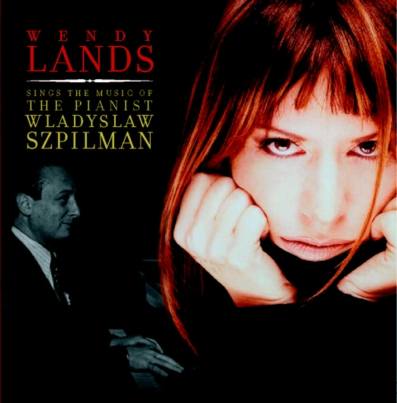

He recently produced a CD with 12 of his father's songs sung in English by Montrealer Wendy Lands (Wendy Lands Sings The Music Of The Pianist, on the Hip-O label).

When the Germans bombed the radio building in Warsaw in 1939, Szpilman was in the middle of Chopin's Nocturne in C-sharp minor. He resumed playing it six years later when the war ended. Sony has issued five CD's and CD sets of Szpilman playing Bach, Brahms, Schumann, Rachmaninoff and his beloved Chopin. In the post-war years, Wladyslaw Szpilman continued to perform classical music as part of a duo with the violinist Bronislaw Gimpel, and later with the Warsaw Piano Quintet until 1986.

His belated fame as a memoirist will, ironically, assure his fame as a musician.

by JUDY STOFFMAN Toronto Star Mar. 1, 2003

Photo jens.wunderlich@t-online.de

Jewish Journal Los Angeles

2003-01-17

Memory Through Music

Wladyslaw Szpilman’s jazzier tunes have made their way onto a new CD, thanks to his son, Andrzej.

by Naomi Pfefferman, Arts & Entertainment Editor

When Andrzej Szpilman was 12, he furtively rummaged through a chest high on a shelf of a closed wardrobe in his Warsaw home. Inside the closet, he found 10 copies of a book and, recognizing his father as the author, hid one in his third-story bedroom. “I read it and received a shock,” said Andrzej Szpilman, 46, a dentist and record producer who immigrated to Germany in 1983.

The book was “Death of a City,” his father, Wladyslaw’s, grittily brutal, dispassionate 1946 memoir of hiding in and around the Warsaw Ghetto. Since Roman Polanski turned the book into a searing film, “The Pianist” — which won four National Society of Film Critics Awards and is up for two Golden Globes on Sunday — Szpilman has become one of the best-known Holocaust survivors in history.

The book was “Death of a City,” his father, Wladyslaw’s, grittily brutal, dispassionate 1946 memoir of hiding in and around the Warsaw Ghetto. Since Roman Polanski turned the book into a searing film, “The Pianist” — which won four National Society of Film Critics Awards and is up for two Golden Globes on Sunday — Szpilman has become one of the best-known Holocaust survivors in history.

But on that fateful 1968 day, his dramatic story was news to his son. “He had never once spoken of his experience,” Andrzej Szpilman said. “He never even told me he was Jewish. I think it hurt him to talk about it, because he survived and all his family perished.”

More than three decades after he discovered “The Pianist” hidden in a wardrobe, Andrzej Szpilman has made it his mission to bring his father’s life story out of the closet, literally. In 1999, he spearheaded the reissue of the memoir, which had been banned by the communist regime and ultimately captivated Polanski. When Polanski’s screenplay depicted his father only as a virtuoso pianist, he produced CDs highlighting his father’s work as a classical composer and the author of more than 500 pop songs.

The latest, “Wendy Lands Sings the Music of The Pianist Wladyslaw Szpilman,” recently released by Universal’s Hip-O Records, is a well-received collection of jazzy ditties Szpilman (1911-2000) wrote from the 1930s to the 1960s. “In the film, we see [Poles] helping my father because they knew his Chopin performances, but the real reason most people knew him and hid him was from his hit songs,” his son said. “He owes his survival to this kind of music.”

In April, with his friend, Sherman Heinig, a German music industry veteran based in Los Angeles, Andrzej Szpilman brought in producer/arranger John Leftwich, who had worked with Rickie Lee Jones. Together, they hired writers to create new, English-language lyrics and auditioned about 30 singers before selecting Canadian-born chanteuse Wendy Lands. The venture is unusual because few scripted films have been able to generate nonsoundtrack albums, according to Variety.

Andrzej Szpilman said he initially invested his own money in the project because his father, while famous in Poland, never had the chance to promote his work in the West. “His career was essentially [stunted] by the Nazis and then the communists,” he said. “But it was painful for me that people thought of his music as only good enough for the Polish market. It’s my ambition to make it popular to a worldwide audience. That’s one way I can honor his memory.”

When Andrzej Szpilman began working on reissuing “The Pianist,” he said his father, then in his late 80s, wasn’t interested in the slightest. “He said, ‘Do whatever you want, but no one will read it,’” his son recalled. Instead, the book became a critically acclaimed bestseller published in 20 languages.

Wladyslaw Szpilman did agree to help publicize the memoir by appearing at book signings and speaking to readers, the first time his son ever heard him talk about the war. “But it was strange,” he said. “He hadn’t read the book in 50 years — in fact he never re-read it — but when he spoke he used the exact same sentences he’d written in ‘46. Like the book, his tone was detached. He sounded like a computer.”

Nevertheless, the elder Szpilman was pleased when the book drew Polanski’s attention and that of Dr. Noreen Green, artistic director of the Los Angeles Jewish Symphony, who conducted the 2001 world premiere of a piece mentioned in the memoir. In the book, Szpilman describes a Gershwinesque “Concertino for Piano and Orchestra” he wrote while languishing in the Warsaw Ghetto. “What struck me was the discrepancy between the wonderful, optimistic music and the terrible conditions under which it was written,” Green said.

Andrzej Szpilman — who included the piece on a CD, “Music Inspired by the Motion Picture ‘The Pianist’” — believes the breezy “Concertino” provides clues to his late father’s psychology. So do the upbeat songs, featured on the Lands disc, Szpilman wrote during the Holocaust and the communist regime’s anti-Semitic purge of 1968. “My father didn’t like to talk about these things, but writing music was his way of coping,” his son said.

“The Pianist’s Story” – An Evening With Andrzej Szpilman

On May 14, 2003 Andrzej Szpilman, son of Wladyslaw Szpilman – The Pianist, was featured for an evening of talk and music at the  Polish Embassy in Washington, DC. The event was co-sponsored by The Thursday Dinner Society as inspired by Polish King Stanislaw August Poniatowski. Mr. Szpilman (left) addressed the audience at length concerning the life and times of his now famous father. He told the very interesting story of how and why his father wrote the book The Pianist: The Extraordinary True Story of One Man’s Survival in Warsaw, 1939-1945. Recently the book was made into the celebrated and internationally acclaimed movie The Pianist by director Roman Polanski.

Polish Embassy in Washington, DC. The event was co-sponsored by The Thursday Dinner Society as inspired by Polish King Stanislaw August Poniatowski. Mr. Szpilman (left) addressed the audience at length concerning the life and times of his now famous father. He told the very interesting story of how and why his father wrote the book The Pianist: The Extraordinary True Story of One Man’s Survival in Warsaw, 1939-1945. Recently the book was made into the celebrated and internationally acclaimed movie The Pianist by director Roman Polanski.

Also recounted were many personal and professional anecdotes and vignettes on all aspects of Wladyslaw Szpilman’s life which held the audience spellbound for over one hour.

The Szpilman presentation was followed by a lively and very informative question and answer period as well as an interlude of entertaining piano music and a sumptuous Polish buffet.

text and photographs by Richard P. Poremski

Published originally in Polish American Journal, Buffalo, NY.

"Charming, effervescent, and strikingly American"... (Bilboard)

..."amazingly cool..." (The Holywood Reporter)

From Universal Records

SONGS COMPOSED BY

WLADYSLAW SZPILMAN

12 popular songs wonderfully performed by Wendy Lands

SONGBOOK

“My memories of you”

Sixteen selected songs by Wladyslaw Szpilman

by Boosey & Hawkes Publishers

Some of Wladyslaw Szpilman's most popular songs from the 30s to the 70s have been recorded on the new disc "Wendy Lands Sing the Music of the Pianist Wladyslaw Szpilman". A selection of these timeless ballads are now published in their original version with piano accompaniment, for singers everywhere with newly commissioned English language lyrics by David Batteau, Michael Ruff, Carol Connor and others.

Learn about concert works by Wladyslaw Szpilman published by Boosey & Hawkes

Wladyslaw Szpilman

Suite : The Life of the Machines (1933). for piano solo

Boosey & Hawkes 2004

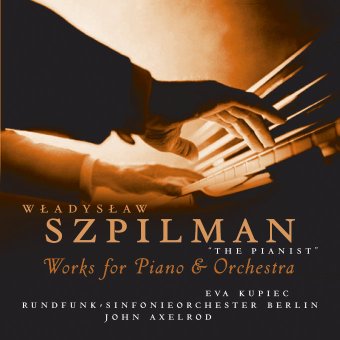

Now from SONY Classical

(Nr.: CD 93516)

in the USA from allimportmusic: CD Nr. 656276 $ 15.99 - SONYC 93516 NL

Wladyslaw Szpilman Works for Piano & Orchestra

Concertino for piano and orchestra, Waltz in the Olden Style*, Paraphrase on an Original Theme*, Introduction to a Film*

Little Overture, Ballet Scene*, Suite "The Live of the Machines"*, Three Little Folk Song Suites*

Ewa Kupiec - Piano, Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin, Director - John Axelrod

Recorded in Berlin on 26-28th June 2004, Published in first edition by Boosey & Hawkes in 2004

* World Premiere on CD

Available from SONY CLASSICAL

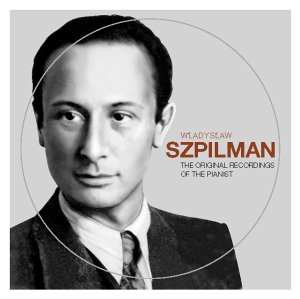

Wladyslaw Szpilman: Original recordings of the pianist

W. Szpilman plays works of Szpilman, Bach, Rachmaninow, Chopin a.o.

![]()

Wladyslaw Szpilman´s Planet

Num : 9973 Name : SZPILMAN Epoch of the osculating orbital elements (Modified Julian Date = Julian Date - 2400000.5) : 53400 Semi-major axis (AU) a : 2.5307511 "e" Eccentricity : 0.17139580 "i (deg)"Inclination (degrees, J2000 ecliptic) : 1.49867 "W (deg)" Longitude of the ascending node (degrees, J2000 ecliptic) : 104.48204 Node : 297.24751 "M (deg)" Mean anomoly (degrees) : 222.7616900 H : 14.20 G : 0.15 Ref : Minor Planet Center MPC40288 Discovery date : 1993 07 12

Discovery site : La Silla

Discoverer : Elst, E. W.