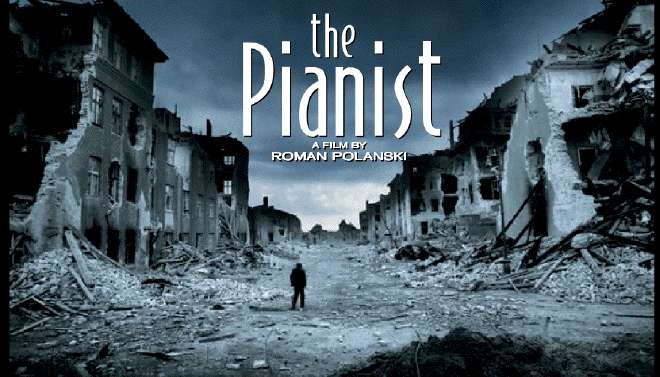

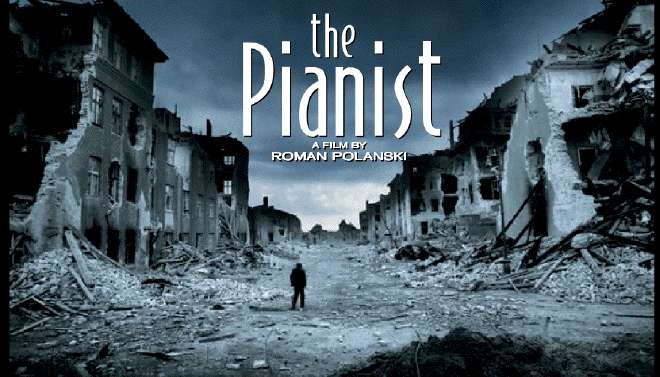

LATEST NEWS TO "THE PIANIST" - A FILM BY ROMAN POLANSKI

Cannes 2002

55th Film Festival

15-26 May 2002

Grand Théâtre Lumière - Friday, 24. May, 9 p.m.

LATEST NEWS TO "THE PIANIST" - A FILM BY ROMAN POLANSKI

Cannes 2002

55th Film Festival

15-26 May 2002

Grand Théâtre Lumière - Friday, 24. May, 9 p.m.

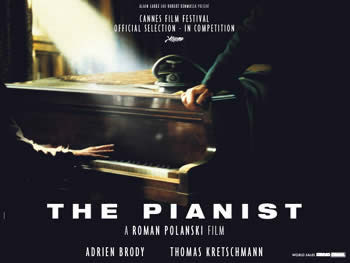

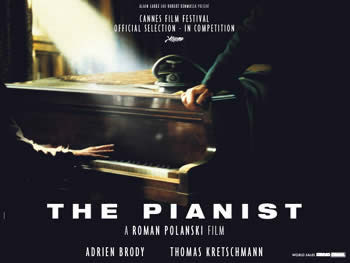

Adrien Brody in:

The Pianist

Directed by Roman Polanski

Script

Ronald Harwood

Roman Polanski

based on the book

by Wladyslaw Szpilman

Homepage of "The Pianist" by Wladyslaw Szpilman (http://www.thepianist.info)

The extraordinary story of one man's survival in Warsaw1939 - 1945

Cast

Adrien Brody

Ed Stoppard

Emilia Fox

Frank Finlay

Julia Rayner

Jessica Kate Meyer

Maureen Lipman

Thomas Kretschmann a.o.

Original music by

Wojciech Kilar

Camera by

Pawel Edelman

Art Direction by

Allan Starski

Costume Design by

Anna B. Sheppard

Frank Finlay, Julia Rayner, Dr. Halina Szpilman, Ed Stoppard, Maureen Lipman, Jessica Kate Meyer, Emilia Fox

Official Homepage of the movie by Canal+

Sunday Times

May 12, 2002

Polanski returns to face Nazi demons

by Richard Brooks, arts editor

THE film director Roman Polanski, who fled the United States in 1978 after being charged with having sex with a 13-year-old, will try to revive his flagging career with his first movie to be shown at the Cannes Film Festival for more than 25 years.

The Pianist, based on the book of the same name, is the most eagerly awaited film at the festival, which opens this week, and possibly the most controversial. It will also be Polanski's most personal movie in a 40- year career.

The film's central character, a Jewish pianist, lived through the Holocaust like Polanski, losing close relatives in the concentration camps. Based on a true story, it tells how Wladyslaw Szpilman was playing Chopin on Warsaw radio when the Germans marched into the station's building.

While Szpilman was sheltered by Poles and even a German officer in the Warsaw ghetto, the rest of his family was taken to Treblinka. He survived, dying two years ago aged 89; members of his family were executed. Polanski, born in France of Jewish Polish parents, lost his mother in Auschwitz. He survived after escaping from a Krakow ghetto through a small hole in the barbed wire cut by his father. During the war he lived with a Catholic family.

Polanski, who was offered a chance to direct Schindler's List but left it to Steven Spielberg, only recently admitted that he was "ready to face again that nightmarish period" by making The Pianist.

"The Pianist is an incredibly important film for Roman," said Ronald Harwood, who has written the screenplay. "Yet, if it is a catharsis for him, he virtually hides it."...

Friday June 22, 2001

The Guardian

In the ghetto with Polanski

For his latest film, the Chinatown director rebuilt the ruins of occupied Warsaw in the Babelsberg studios in Berlin. Ronald Harwood, who wrote the movie's screenplay, was with him

The moment a screenplay is finished, the writer is detached from all that follows: the preparation, the casting and finally the shooting of the film. You do all that work, and then someone taps you on the shoulder and says: "Excuse me, but I get to do the next bit." That someone is, of course, the director.

Perverse as it may sound, the experience can be immensely pleasurable, depending on who taps you on the shoulder. When Roman Polanski did the tapping, I enjoyed it hugely. Polanski telephoned me in the spring of 2000. He had admired the Paris production of my play Taking Sides, which has just been filmed by the great Hungarian director, Istvan Szabo. He thought I might be the person to write the screenplay of a book he wanted to make into a film.

The book is called The Pianist - a compelling account by Wladyslaw Szpilman of his gruesome experiences in the Warsaw ghetto, from which he managed to escape. Once outside, he was sheltered by courageous Poles until he was forced to fend for himself, suffering hunger and illness. Then he was befriended by a German officer, who brought him food and helped him to survive until he was liberated. Szpilman died last year, aged 88. I read his book in one sitting, telephoned Polanski and said yes.

We met for the first time at his Paris apartment. I was taken aback by his youthful appearance. He is 68 now, but still slim and energetic. He has been married for nearly 20 years to the actress Emmanuelle Seigner, and they have two children.

We became friends instantly. He is great fun to be with, his energy is infectious and his changes of mood electrifying. His impatience is alarming. He loves limericks, the dirtier the better. We hardly mentioned The Pianist.

It was known that Polanski had turned down an offer to direct Schindler's List, a film set in the Krakow ghetto from which Polanski himself escaped at the age of six. His parents and sister were taken off to the camps. (His father and sister survived but not his mother.) His reasons were that the events would have been too close to him, the people too familiar. He had known most of them and a few were still alive. But The Pianist offered a means of expressing some of his own feelings about his appalling childhood. He decided we should go to Warsaw, mainly to look at the horrific archive footage, and to inspect the place where the Jews were walled in.

On three successive days, we sat in a viewing theatre to watch the grainy black- and-white record of the brutal destruction of Warsaw's Jews. Then we were taken on a tour of what had been the ghetto. Most of the area has been turned into a park with a memorial. Only the infamous hospital, where so many were slaughtered, remains, and is now a school. It was a depressing few days. On the way back to Paris, Polanski said: "Okay, start writing."

The outstanding virtue of Szpilman's book is its amazing objectivity. Polanski and I were determined to preserve the author's approach. But we were also determined not to use a voiceover, not to have Szpilman as narrator. This, of course, presented problems. Szpilman is alone for much of the story. He has no one to confide in. So the emotional content had to emerge from the action.

When I delivered the screenplay, Polanski's reaction was generous and enthusiastic. But he added ominously: "You know what we do now? We lock ourselves up for a month until we're totally happy."

He rented a large country house near Rambouillet. We worked every day. We'd act out scenes aloud and when he wasn't sure I understood exactly what he wanted, he'd draw the location or the prop or the camera angle. He is a gifted artist so his sketches were enormously helpful. When I made a suggestion that wasn't to his liking, he'd react as though I'd insulted his wife. "You crazy? That's terrible!" he'd cry. "Let's have a coffee." And when I suggested something of which he approved, he would be equally extreme: "That's great, my God, that's great. Let's have a coffee!" We drank a lot of coffee.

Press conference in Babelsberg

Much of the time he was dredging his own memories for details and incidents. There was one in particular I remember. I had reproduced the moment in the book when a Jewish policeman saves Szpilman from boarding a cattle truck bound for Treblinka. He describes himself running from the scene. "No!" Polanski said. "I'll tell you what happened to me. It'll be better." Apparently, he too was saved in a similar manner but when he'd been pulled out from the crowd and started to run, the policeman shouted: "Walk! Don't run!" So we changed it. In the film Szpilman walks slowly towards the gates while the Germans herd his family and all the others into the trucks. It was a reality I personally could not have invented.

Despite the subject matter we laughed a lot, making dreadful jokes about Jews, Poles and Germans. It was the only way to get through. A month to the day later, we finished. Once back in Paris, he presented me with a gift: an espresso coffee machine.

Because Szabo was still filming my play Taking Sides at the Babelsberg studios in Berlin, Polanski was keen to know what the facilities were like. He flew to Berlin and came back bubbling with enthusiasm. "It's like a Hollywood studio in the old days," he said. It was decided to build streets and ruins on the back lot at Babelsberg. The remainder of the film was to be shot in Warsaw. But he still hadn't finished with me: "Let's do a polish at my place in Ibiza."

Together with my wife, his children (Emmanuelle was in a play in Paris), a friend and a couple of staff, we flew to Ibiza where Polanski has built a villa. Here, we did the final polish, changing a word here, a stage direction there. It took a couple of days. During the weeks that followed, I saw him in Paris, or he'd telephone me in London. He'd still be bothered about the odd line of dialogue and ask for a change, usually just one word. And he was keen that I should visit him again. I guessed another word needed changing, so I flew to Warsaw to see him at work.

Checking in at an airport is an exhilarating experience in comparison to watching a film being made. Only two people know what's really going on - the director and the lighting cameraman. There are endless periods when nothing seems to be happening. Then, intense activity as the actors are called for a shot that may last less than a minute. Then another endless wait. For the onlooker, it is exhausting. It was overcast so Polanski was obliged to break off from filming outdoors to shoot a family scene in a studio. Clearly invigorated by the process of filming, Polanski is surprisingly calm and polite throughout. Nevertheless, everything is charged with urgency. He conducts the proceedings in Polish, English and French.

The next day, the sun blazed down and he returned to the Umschlagplatz - meaning "the place of deportation", where the Jews of Warsaw were assembled before being sent to their deaths at Treblinka. The reconstruction of this dreadful place has been superbly achieved. A thousand extras sat or stood about exactly as the Jews did 60 years ago in unbearable heat with their star of David armbands, suitcases and bundles. Polanski, slightly hunched, eyes narrowed, darts purposefully here and there, giving instructions, refining the action, attending to the minutest details. Occasionally he mutters, "I don't know how to do this," and then instantly finds a solution with the help of his lighting cameraman, Pawel Edelman.

But there is something surreal about the proceedings. While the horror is being re-enacted, I sit under a brightly-coloured parasol with the actors playing the Szpilman family: Maureen Lipman, Frank Finlay, Ed Stoppard, Julia Rayner and Katya Meyer. We chat about mutual friends and British theatre. Adrien Brodie, who plays Szpilman, says he wants to buy a cottage in upstate New York. Then they are called on to play a short scene amid the crowd. Suddenly they are in character, weighed down by circumstance, taking direction from Polanski as he gently guides their performances.

Polanski's gift is to tell the story without affectation and without over-emphasis. His background is in the theatre and so he respects the script, insisting on the dialogue being spoken as written. He understands the needs of actors. He is well read. His taste is not of the what's-popular-now variety, but relies on values that are older and unashamedly European. I look forward to seeing the film. And I look forward to him tapping me on the shoulder again at the critical moment.

NY Times

September 6, 2001

ARTS ABROAD

Polanski Film About Holocaust and Suffering in Poland

Polanski Film About Holocaust and Suffering in Poland

By PETER S. GREEN

WARSAW — Roman Polanski's life has been shaped by the maxim that art often has its roots in great suffering. After fleeing the oppressive rule of Communism in his native Poland in 1961, Mr. Polanski made two of his most powerful films, "Repulsion" and "Cul-de-Sac." Later, after Charles Manson killed Mr. Polanski's wife, the actress Sharon Tate, and their unborn child in 1969, he went on to make his bloody adaptation of "Macbeth."

But it has taken him almost six decades to come to terms with another period of suffering: the time he spent in the Jewish ghetto in Krakow, which he escaped at age 6. He is now almost finished with a project that has led him to return to that era: an adaptation of "The Pianist," Wladyslaw Szpilman's dispassionate autobiographical account of surviving the Warsaw ghetto.

Throughout the filming here, Mr. Polanski, 68, kept a low profile, shunning most publicity for the movie, which is being made in English and has been largely financed by France's Canal Plus cable television channel. It is produced by Gene Gutowski, an old friend, who produced Mr. Polanski's earliest films and is himself a survivor of German-occupied Warsaw.

Friends and observers say "The Pianist" is a crucial film for Mr. Polanski. His recent work, including "The Ninth Gate," starring Johnny Depp, has failed critically and commercially.

"For Polanski it is a question of his career," said Andrzej Kolodynski, the co-editor of Kino, a Polish film magazine. "If this is a flop, his career is finished. Poor Polanski."

That may or not be true, but Mr. Polanski himself recognizes that the stakes are high. "It is the most important film in my career," he told Kino. "Obviously, emotionally it is a work which cannot be compared with anything I have done so far, because it takes me back to the times which I still remember."

In "The Pianist" Mr. Polanski is dealing with a book that is stunning in its brutal simplicity. From Poland's defeat by Hitler's army in September 1939 to the gradual imprisonment of all of Warsaw's Jews in a starving, fetid ghetto, Szpilman describes not only the cruelty and degradation inflicted by the Nazis but also the horrific inequities among the Jews themselves.

As shells fell on Warsaw, Szpilman, then a young Jewish pianist and composer, played the last live music — Chopin's Nocturne in C sharp — heard on free Polish radio before the German artillery destroyed the transmitter. Later, he tells how he survived, playing piano for scraps of food in a ghetto cafe where rich Jews passed their final hours. He escaped while on a work detail and hid in occupied Warsaw.

At the war's end, Szpilman, who died last year at 89, returned to Polish radio and immediately wrote his memoirs. They were soon turned into a film, shot among the real ruins of Warsaw. Originally called "Robinson Warszawski" (Warsaw Robinson) it was retitled "Unvanquished City" by Communist censors who, among other changes, inserted shots of residents welcoming the Red Army. No original cut is known to exist.

Mr. Polanski first learned of "The Pianist" when it was recently republished in Polish. (It was published in the United States by Picador USA in 1999.) "I wanted to make a film about the Holocaust for a long time," Mr. Polanski said at a news conference. "Szpilman's book is the text that I have been waiting for, because `The Pianist' is a testimony of human endurance in the face of death and a tribute to the power of music and the will to live. It breaks lots of stereotypes and is a story told without the desire for revenge. Immediately after reading several of the first chapters, I knew it was the subject of my next film."

Steven Spielberg offered Mr. Polanski the opportunity to direct "Schindler's List," but Mr. Polanski turned it down, Mr. Gutowski said, because he felt that filming in the remains of the Krakow ghetto would be too painful.

"The Pianist" is filled with scenes familiar to Mr. Polanski, who escaped the Krakow ghetto through a hole cut in the barbed wire. The book opens with Szpilman's account of trying to rescue a child who was smuggling goods into the ghetto. Pursued by a German policeman as he was trying to slip back into the ghetto through a hole in a wall, the child became stuck. "When I finally managed to pull the child through, he died," Szpilman writes."His spine had been shattered."

Preserving the grittiness of this memoir's reality has been his greatest task during the filming, Mr. Polanski said. "I think the biggest challenge is the visual side of the movie," Mr. Polanski explained in a Polish magazine. "I want to avoid the shine that every film has, but on the other hand, I do not want to pretend to be making a documentary of that period."

In the center of Warsaw today, only a half-dozen buildings remain from the wartime ghetto, so "The Pianist" was shot partly in the city's outlying Praga district and partly in the Babelsberg film studios in Germany, where large portions of the ghetto were recreated. The ruins of the ghetto, which was bombed by the Germans after the Jewish uprising, were filmed at a former Soviet Army base in eastern Germany, which Mr. Polanski had dynamited to create sufficient rubble.

The film's cast is made up largely of Germans and Poles and a handful of other European actors. Adrien Brody, a young Englishman who starred in Ken Loach's "Bread and Roses," was chosen to play Szpilman. Mr. Polanski and Ronald Harwood, who wrote the script, put together a documentary from Nazi films of the ghetto and screened it for the extras and bit players to prepare them for their roles, Mr. Gutowski said. Some scenes in the filming of "The Pianist," like the Warsaw ghetto uprising, were so brutal that "there were many moments where Roman was visibly upset," he added.

Mr. Polanski's return to his native country to film a Polish tale after nearly 40 years' absence is seen by many as a vindication of Poland's place in the world, and has been the talk of film circles and the subject of features in Polish magazines. At the Lodz Film School, where Mr. Polanski studied, he is regarded as an icon, and the places where he shot his school films are considered landmarks.

It seems that the timing of "The Pianist" could not be better. In July, Poland's president, Aleksander Kwasniewski, apologized on behalf of his fellow Poles at Jedwabne, a village in northeast Poland where hundreds of Jewish residents were murdered by Polish townspeople in 1941.

"I don't want to be cynical," Mr. Kolodynski, the film journalist, said, "but it's a good moment for a film about the Holocaust, because Jedwabne has started an enormous discussion in Poland of accounting with your conscience."

Adrien Brody - "The Pianist"

Ifson.org in may 2001:

Polanski on Holocaust

The scenes refuse to fade and continue to haunt the memory: An old man trembling with cold yanks a bowl of hot soup from a woman, only to have it fall to the ground and spill. An SS officer calmly shoots a boy in the head because he was too terrified to salute. Nazis forcing Jews in Warsaw's ghetto to dance for their amusement.

With this film, now being shot in Warsaw, the Polish director Roman Polanski is for the first time tackling the Holocaust. It is a topic Polanski has so far avoided in his film career, giving up the opportunity to direct Steven Spielberg's Schindler's List as it too closely resembled his own boyhood.

Polanski was able to slip out of Krakow's ghetto and pass himself off as a gentile, but his mother was murdered at the Auschwitz death camp.

But the story of the Polish-Jewish pianist Wladyslaw Szpilman offered Polanski the chance to avoid playing to stereotypes and present the Holocaust not only its full horror, but also full complexity.

"I was searching for a subject from that period that was accurate without being too simple," Polanski said in a recent press conference in Warsaw. "After reading several chapters (of Szpilman's bestselling autobiography) I knew I had my subject," he said.

Szpilman was not only a witness to the collapse of independent Poland in September 1939, he created one of its most poignant symbols: as German bombs fell and knocked out Polish radio, Szpilman played the Nocturne in C sharp minor by Fredryk Chopin, Poland's greatest composer, in a live broadcast. Along with half a million other Jews Szpilman was herded into a ghetto capable of holding 100,000 people.

The autobiography and film recreate the atmosphere of the cafes where Szpilman played to earn money to feed his family. And also the suffering of residents, who, walled-off from the rest of the city, died of hunger, exposure and disease.

Szpilman recounted the brutality of the Nazis, describing the sounds of a chair and the old invalid in it hitting the pavement after being thrown from a fifth-storey window. But in the end it was a German officer, who appreciated his music who saved Szpilman, hiding and feeding him in Warsaw's ruins.

A keen and honest observer, Szpilman also recounted the deplorable actions Jews and Poles were driven to in order to survive. "Szpilman was objective, not sentimental," said Polanski. "He showed Poles who were good and those who were wicked, Jews good and wicked, Germans good and wicked. "What is most important is that the book is very positive. After having read it, one is not depressed because it is full of hope. At the end we are convinced that human nature, despite everything, is good."

In order to give the film a realistic feel, the director of Chinatown returned to Warsaw to shoot part of the film. None of the ghetto remains. The Nazis flattened it following an uprising by the Jews but the eastern half of Warsaw escaped the war more or less intact.

The old Praga neighborhood has changed little since the war, with narrow streets, old street lamps and tram lines, and the occasional bullet-hole and pre-war advertisement still visible on some buildings. "It is not a fictionalized account, it is very close to reality, almost a documentary," said the film's chief make-up artist, Didier Lavergne.

Some of the characters in the film are not being played by professional actors, to give the film a rougher feel. Polanski originally wanted an amateur to play Szpilman, but he eventually settled on American actor Adrien Brody, of Bread and Roses and The Thin Red Line.

Shooting of the 38 million euro (33 million dollar) film is due to be completed in November.

Szpilman died last year at the age of 88.

Polanski playing his most important tune

Roman Polanski ... serious about his new film

By JACK KINDRED

Berlin: In what he describes as "the most important film of my life," Roman Polanski is directing Der Pianist at Berlin's Studio Babelsberg, based on a true story of a brilliant virtuoso's survival in the Warsaw ghetto during the Nazi occupation.

The $US41 million ($A79.53 million) European co-production with an English-language soundtrack is based on the memoirs of Polish pianist Wladyslaw Szpilman, whose musicianship saved him from almost certain death in the Warsaw ghetto.

Banned by the communist government, Szpilman's account of his ordeal, Das wunderbare Ueberleben (The Miraculous Survival), was reissued two years ago, just one year before the noted pianist died. He was the only one in his family to survive the Holocaust.

Polanski heard Szpilman play at a concert in Warsaw a decade ago without being aware of the musician's past. But when he discovered Szpilman's book, he found what he had been looking for at last. "I had searched for decades for a model parallel to my life, which I couldn't film myself," Polanski told the trade publication Film Echo.

After five weeks of shooting ends at Studio Babelsberg and environs, the production moves to Warsaw for 11 weeks, fulfilling Polanski's wish to film once again in his homeland.

At first, the director wanted to shoot the entire movie in Poland, but was unable to find suitable locations and sufficient studio capacity.

Poalnski was born on August 18, 1933 of Polish-Jewish parents. When he was eight Polanski's parents were taken to a Nazi concentration camp where his mother died. The terrified child escaped from the Krakow ghetto just before it was razed by the Nazis and wandered about the countryside, being taken in by a number of Catholic families.

He had many narrow escapes and witnessed many horrors before returning to Krakow toward the end of the war, where at the age of 12 he was finally reunited with his father.

Polanski's emotional experiences in the Krakow ghetto during his formative years "appear in every scene and guarantee the movie's authenticity and realism," said Ronald Harwood, who adapted the script from Szpilman's book.

The Nazis imprisoned the musician and his entire family in the Warsaw ghetto and submitted them to much suffering and humiliations. He alone was the only one to avoid deportation to the death camps and hid among the ruins of the ghetto.

A German officer, who was a music lover, in the end saved Szpilman's life.

Polanski has lined up a distinguished crew. Harwood had written the screenplay for Hungarian director Istvan Szabo's Taking Sides, based on Berlin Philharmonic director Kurt Furtwaengler's relations with the Nazis and efforts to save the lives of his Jewish musicians. Polish set designer Allan Starski and British costume designer Anna Sheppard, created the authentic look for the acclaimed Holocaust movie, Schindler's List.

Polanski's long-time colleague, Gene Gutowski, the producer of Polanski's horror-parody Dance of the Vampires, was co-producer, backing up producers Robert Benmussa and Alain Sarde. Camerman Pawel Edelman's credits include the historic Polish epic, Pan Tadeusz.

In the search for an unknown actor, Polanski selected 30 for screen tests out of the thousands who had responded to advertisements in the London newspaper, The Guardian, and the Net. But he finally decided on a professional, the American actor Adrien Brody, who starred in the war film, The Thin Red Line.

Brody, who took piano lessons as a child from his mother, practised diligently in preparation for his role. Other leading players are Thomas Kretschmann, the German officer who saves Szpilman's life, while British actors Frank Finlay and Maureen Lipman have supporting roles.

The soundtrack is to include pieces from Frederick Chopin, and other compositions from the standard pianistic repertoire, as well as original compositions from Wojciech Kilar in the film score.

Der Pianist is the third big European production prepared and partly filmed at the former East German Defa Studios, following its reconstruction and revival as a film and television production centre. Other recent Babelsberg productions include Enemy at the Gates, the opener at this year's Berlin International film festival, and the above mentioned Taking Sides.

DPA smh.com.au sat. March 10,2001

Polanski, the Once and Future Auteur

New York Times, 16.1.2000

International Herald Tribune, 18.1.2000

By ALESSANDRA STANLEY

OME -- SEATED at a corner table at Il Matriciano, one of his favorite haunts during his dolce vita of the 70's, Roman Polanski was discussing his desire to make an important, lasting film. Almost impatiently, he explained that his latest release, "The Ninth Gate," was not it.

" 'Ninth Gate' is fun, it's nice, I think it's a good movie, but after all, what is it about?" asked Mr. Polanski, the 66-year-old Polish-born director whose repertory includes "Repulsion," "Rosemary's Baby" and "Chinatown."

"It's like every other movie that is made nowadays. It may be different in style, but it doesn't make any important statement."

Actually, "The Ninth Gate," an occult thriller opening March 17 that features satanic rituals, exotic locales and gruesome deaths, is not even very nice. Mr. Polanski jokingly described it as "an advertisement for hell."

Adapted from a novel by the Spanish writer Arturo Perez-Reverte, the film stars Johnny Depp as a brooding, Scotch-swilling, chain-smoking scavenger of rare books; Frank Langella as a rich, literally demonic book collector; and Lena Olin as a devil-worshiping society hostess, all of them seeking a key to "the ninth gate," which, perhaps not surprisingly, leads to Satan.

Emmanuelle Seigner, the French actress who is Mr. Polanski's wife, plays a mysterious guardian angel. She also starred in two previous Polanski films, "Frantic," a 1988 thriller starring Harrison Ford, and "Bitter Moon," a 1992 movie about sexual obsession gone awry.

Together since 1985, the couple live in Paris and have two small children, and it is obvious that Mr. Polanski relishes late fatherhood, describing with amused pride his 6-year-old daughter's fascination with "Dance With the Vampires," a 1997 musical performed in Vienna, and based on his 1967 film, "The Fearless Vampire Killers." "She has seen it already 10 times," he said. "She plays the tunes on the piano and sings the songs, doing shows at home."

His wife called him from Paris on his cell phone during dinner, and he listened attentively as she described her own dinner with fashion models from the Paris collections. "Hmmm, models, eh?" he interjected with a laugh. "I should be there."

Mr. Polanski was more reluctant to discuss his film, which was poorly received even in France, a nation that tends to be generous to auteurs. He was in Rome last fall for rehearsals of an Italian stage version of "Amadeus," which he is directed, and was perhaps stung by the negative reviews back home. Libération, called his movie "painful to watch."

He chose "The Ninth Gate," he said, because he liked the black humor and the occult mystery within the plot, because he wanted to work with Johnny Depp and, most of all, because he could make it without delay. His last film was "Death and the Maiden," in 1994. "This was something that could be done quickly, I needed work, I had to do something. It was too long a time since my last film, a lot of projects were canceled."

James Hill for The New York Times

"I needed work, I had to do something," says Roman Polanski, about his most recent film, the occult thriller "The Ninth Gate," starry Johnny Depp.

It is hard to imagine that Mr. Polanski -- whose film career spans 40 years and continued successfully even after the horrifying murder of his wife Sharon Tate by the Manson gang in 1969, and after a statutory rape charge drove him to become a fugitive from American justice in 1977 -- feels the kind of restless anxiety that fuels younger, less-accomplished filmmakers.

Mr. Polanski chose to flee Los Angeles, but he has not shaken off the pressure of Hollywood.

"Before in Hollywood, even if you did not make a commercial success but the film won awards or was well received or the community had a conviction it was a good film, there would be satisfaction in the studio," he said, describing with nostalgia an era when he was a dashing celebrity and a respected artist in Hollywood. He added: "Rushes were always seen by the whole studio, there was pride taken in achievement even if it didn't strike a jackpot. Now the only thing that counts is the dollar, and on a huge scale. Nobody cares about a film that pays for itself and brings in a marginal profit. They all want a bonanza."

His friends say Mr. Polanski is merely realistic about an industry that is still overwhelmingly controlled by Hollywood. "It is hard enough to make a hit in the United States; to operate from Paris makes it all the harder," explained Andrew Braunsberg, a Vienna-based producer and close friend of Mr. Polanski's who has worked with him since the swinging 60's in London. "Nowadays, 99 percent of the settings for major films are either in the United States or outer space."

Mr. Polanski's bitterness may also have been prompted by a major studio's decision to drop one of his more ambitious projects: a film version of Mikhail Bulgakov's classic 1930's novel set in Communist Moscow, "The Master and Margarita," which Mr. Polanski wrote himself. He described the script as "the best thing I ever managed to adapt -- and it seems like an unadaptable novel," but he said that the project was scrapped soon after the Berlin Wall fell by executives at Warner Brothers, who decided that Mr. Polanski's budget was too costly.

He said he began working on it more than 10 years ago. "It is a good script. It so good that people keep telling me even now to come back to it."

He sighed wearily. "I think it is a bit late now. The book's Moscow scene has vanished and finally it wasn't that important," he said, referring to Soviet Communism. "It did not leave the same stain on history as the Shoah."

He added, "If I were to make something about those times I would rather go for the Holocaust or my childhood."

The two are entwined. When he was a young boy in the ghetto of Cracow, his mother was taken away to a concentration camp, where she died. Shortly afterward, he watched as his father was deported by the Nazis. His father survived and they were reunited after Germany surrendered, but Mr. Polanski spent the war hiding among peasants in the countryside.

Mr. Polanski said he had been thinking about making a film about the Holocaust for many years, but could never find the right material. He said he turned down an early offer by Steven Spielberg to direct "Schindler's List" as "a very generous offer but not right for me." Nor was he prepared to make a film of his own youth. "My childhood had no story in a Hollywood sense -- there has to be a denouement or intrigue," he said matter-of-factly. "Or it would have to be fictionalized, and then I would have to be untruthful to the real events." He added rather gloomily that he doubted his childhood would entice major studios. "You don't know these people," he said with a laugh. "They would ask, 'Yes, but who is the girl?' "

Two months after the dinner, Mr. Polanski called to announce a new project he had not felt free to discuss in Rome. He had just reached an agreement to adapt "The Pianist," the autobiography of Wladyslaw Szpilman, a Polish composer and pianist who, like Mr. Polanski, narrowly escaped a roundup that sent his family to the death camps. Mr. Szpilman, now 86, spent the war hiding in the burned-out ruins of Warsaw, scavenging for food and shelter. Toward the end, he was helped by a German officer who appreciated his music and who ended up dying in a Soviet P.O.W. camp. Mr. Szpilman's extraordinary memoir, written in 1946, was suppressed by the Communist authorities for 40 years and was finally published in Germany two years ago and in the United States last year.

"It's the story I've been looking for for years," Mr. Polanski said. He said he did not see it as an echo of his personal tale, despite the haunting similarities, pointing out that Szpilman was 27 and already a famous musician at the start of the war, and that he lived in the Warsaw ghetto, which was far larger than Cracow's. "It was very different -- what happened in Warsaw was on an epic scale," he said, adding dryly, "But I do know the subject."

He said he found the book harrowing, but distanced himself at the same time. "It's a very difficult subject to relive, whether it is your history or not," he said.

Mr. Polanski maintains the same reserve about the crises of his adult life. Even his autobiography, titled "Roman," which he published in 1984, is phlegmatic in describing his reaction to the murder of Sharon Tate, and later the statutory rape charge, which he vigorously denies in the book. "I couldn't equate what happened that day with rape in any form," he writes. Mr. Polanski served six months in prison under psychiatric observation, but fled while awaiting sentencing, convinced he would not get a fair deal from the judge.

Twenty years have passed, and the girl, who is now 35, has said in interviews that she feels Mr. Polanski should be allowed to return, and his friends say the legal obstacles could probably be overturned.

But the director is skeptical. "If I even think about going back, there are immediately articles. So if I went for real you can imagine the number of articles there would be. And I don't want to become the prey of the media again." Mr. Polanski, who said he admired the way Bill Clinton endured the Monica Lewinsky scandal, said he did not think that case helped his own.

"A lot has changed, but the main thing is that the media has taken over the judicial system of the United States," he said. "The outcome depends entirely on what they say and show about you on television. I would have to go back and spend some time there. And I think it would be hell, not from the system itself but from the media. I don't want people hanging outside my door, and antenna dishes in front of my window or on top of some mobile television truck."

What he wants, he said, is an opportunity to make major films. Even, someday, another shot at Bulgakov's novel.

"I first have to make a hit," he said ruefully, "then maybe I'll be comfortable enough to deal with the executives and push the thing through."

Alessandra Stanley is chief of the Rome bureau of The New York Times.